Haiti had been without a president for a week when on Sunday a collection of politicians and business leaders chose an interim leader to fill the void.

The appointment stalled a deepening political crisis in the nation of 10 million — at least for now.

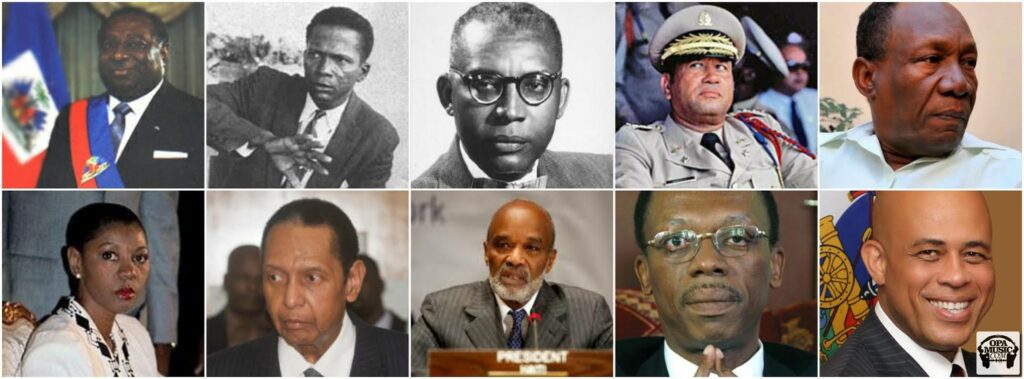

Not that presidents have always been so great for Haiti.

There have been 45 leaders since the country achieved independence from France in 1804, and for the most part they have pillaged and plundered, ruled as despots, stifled opposition, violated human rights and operated with impunity.

“They don’t really want to work for the Haitian people, to improve them,” said Pierre Esperance, executive director of the National Human Rights Defense Network in the capital, Port-au-Prince, in describing what he believes has discredited many of Haiti’s leaders. “They work for themselves once they get to power. They want to steal money.”

On the other hand, Haiti hasn’t been so great for many of its presidents either. A total of 23 have been overthrown, with Jean-Bertrand Aristide (February—September 1991, 1994-1996, 2001-2004) toppled twice.

Henri Christophe (1807-1820), a wildly unpopular, self-proclaimed king, didn’t wait to be toppled. He shot himself to death.

Two rulers were assassinated in office, including Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam (March-July 1915), who sought asylum in the French Embassy during a popular rebellion but was dragged out and dismembered by a mob that paraded his body parts through town.

Dictator Sylvain Salnave (1867-1869) tried to escape insurrection by fleeing to the neighboring Dominican Republic but was extradited, court-martialed on charges of murder and treason, and executed on the steps of the National Palace.

If there is an optimistic take on Haiti’s current situation, it’s that the nation’s most recent president, Michel Martelly (2011-2016), stepped down peacefully Feb. 7 after completing a full term in office. That is a routine occurrence in functioning democracies. But it puts Martelly in an elite club in Haiti.

The present trouble started in October when none of the contenders to succeed Martelly gained a clear majority in polling. The top two were supposed to compete in a runoff, but amid security concerns and allegations of rigging the election was delayed three times as Martelly’s term ran out.

A week of negotiations led to Sunday’s selection of Jocelerme Privert (February 2016-present), a senator and former head of parliament, to serve for 120 days.

Under the best-case scenario, he will organize fresh elections for April 24 with the aim of installing a new president on May 14. Under the worst, the country will succumb to all-too-familiar gridlock. The last time Haiti had an interim government, in 2004, it took two years to hold elections.

Whoever emerges as the next president will face a nation where poverty is widespread, corruption is rampant and basic institutions are in shambles.

Not all of Haiti’s problems can be attributed to bad leadership; meddling and exploitation by France and the U.S. are also culprits. But experts said the right leaders could have at least set Haiti on a steadier course.

“It requires a leader with a certain strength of character,” said James Dobbins, a senior fellow and distinguished chair in diplomacy and security at Rand Corp., who has served as a special envoy on crisis management and diplomatic troubleshooting in Haiti. “Someone who is able to inspire trust across the social and economic spectrum of the country, someone with charisma but also with a communicable sense of integrity.

“That combination has not appeared yet,” he said.

The country’s first leader, Jean-Jacques Dessalines (1804-1806), set a low bar. A former slave, he instituted a harsh system of plantation labor, ordered a massacre of several thousand white Haitians and declared himself emperor. The circumstances of his assassination remain unclear.

“Immediately after independence things fell apart,” said Marc Prou, a professor of Africana and Caribbean studies at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. “Instability became the order of the day.”

There have been moments when Haiti seemed poised for a turnaround, or at least instances when leaders appeared to put the interests of the nation over their own.

Jean Pierre Boyer (1818-1843), the son of a white Frenchman and a former African slave, managed to unify Haiti, which had been divided into a primarily black north and a mulatto south. But he then proceeded to exclude blacks from power, triggering unrest and his ouster.

Fabre Nicolas Geffrard (1859-1867) founded the National Law School, modernized general education, built roads and recruited black Americans to settle in Haiti. But he also eliminated the legislature, awarded himself land and used public funds for personal luxuries. He too was overthrown.

Lysius Salomon (1879-1888) instituted the country’s first postal system, established Haiti’s National Bank and tried to boost agricultural production. But he was toppled in a coup led by Haitian exiles.

Many Haiti observers agree that two-time President Rene Preval (1996-2001 and 2006-2011) tried to rule with fairness and integrity through political upheavals and economic chaos.

“Preval was honest and well-meaning but not effectual,” said Dobbins, the Rand expert. “He was certainly not a leader who was capable of bridging the divide between different groups and forging consensus.”

The competition for worst leader has many entrants, but there is a consensus among historians: Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier (1957-1971).

(EDITORS: STORY CAN END HERE)

He ruled with an iron fist, keeping the population in check with a ruthless militia known as the Tonton Macoute that murdered as many as 60,000 of his countrymen.

Duvalier changed the constitution and in 1964 declared himself president for life. He arbitrarily banned political activity, muzzled the mediass and made the national treasury his personal piggy bank.

His death might have brought some relief, but instead his 19-year-old son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier (1971-1986) took over, extending the family legacy.

Political repression, drug trafficking and the selling of Haitian corpses to foreign medical institutions were hallmarks of his reign, which ended with a popular uprising and a flight to France.

“Thirty years of dictatorship made it difficult to transition to a democratic system,” Prou said.