Beken was born in Port-au-Prince in 1956. At the age of twelve, he lost a leg in a car accident. In Haiti, where resources are scarce, a person with disabilities often faces a lifetime of poverty and marginalization. Fortunately, Beken attended Saint Eternité School, which serves disabled children, and managed to complete high school by nineteen—an achievement beyond the reach of most Haitians. If the song “Bakaloreya” is accurate, Beken might have pursued university education had it not been for the death of his mother.

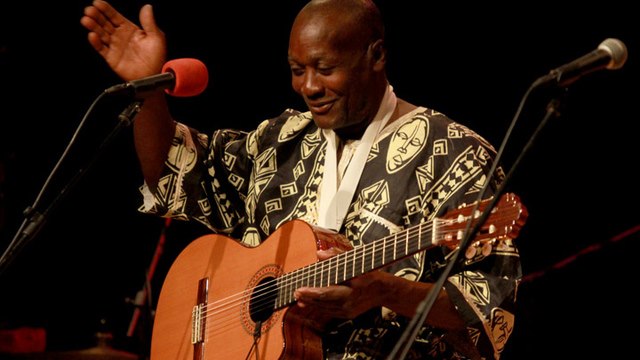

Beken’s musical journey began early, influenced by his father, who regularly sang for a peasant organization. After his accident, Beken picked up a guitar and immersed himself in Haitian music. In his song “Kote’w Te Ye,” he reflects on his long relationship with his wooden guitar, which eventually became his livelihood. Beken’s music falls within Haiti’s troubadour tradition, a genre that, like many European cultural forms, has been uniquely transformed in Haiti. While some troubadours reinterpret international pop music within a Haitian context, others, like Manno Charlemagne, use their music to deliver sharp political commentary, even at great personal risk.

Beken’s lyrics are less overtly political and more reflective, often echoing the collective experiences of his listeners. In Haiti, where suffering is a shared reality, Beken’s songs resonate deeply. His music conveys a message of shared hardship and collective hope, suggesting that his dreams for a better life are also the dreams of his audience.

This empathetic approach has brought Beken several cycles of success, particularly in the 1980s when he toured the United States. However, in the Haitian music industry—where piracy has been rampant long before the digital age—fame does not equate to financial security. Beken’s old records are widely sold across Port-au-Prince, but he sees little benefit from these sales. Due to restrictive U.S. immigration policies, Thirty Tigers’ efforts to bring Beken to the United States since 2013 have been unsuccessful. As a result, Beken likely continues to sing for his supper wherever he is today. He has expressed a humble contentment, saying, “I don’t need anything—nothing! Just a guitar, a bottle, and some old pen, and I am going to sing a lot. Beken has a lot of things in his head that he has not yet sung.”

Beken’s story is one of resilience and the enduring power of music to capture the soul of a people. Through his songs, he continues to reflect the struggles and hopes of the Haitian people, serving as a poignant reminder of the unbroken spirit that defines their cultural heritage.

– Madison Smartt Bell