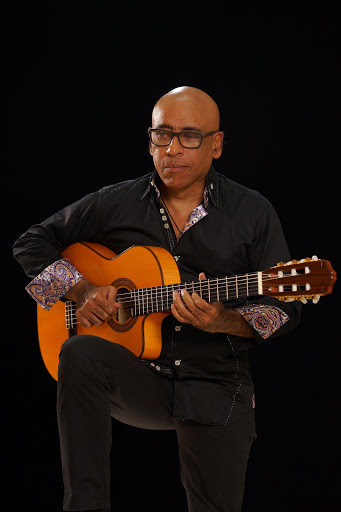

Jacky Ambroise, was born and raised in Haiti, and until founding Strings in 1996, made his living playing traditional Haitian Compas. That style, best described as a slow guitar-centered merengue, with the congas played distinctively offbeat, originated in the ’50s and is the dominant musical genre in Haiti today. But while many compas artists have strived to update their sound by incorporating drum machines and synthesizers, as well as elements from American hip-hop and R&B, Strings has looked eastward across the Atlantic for inspiration, forging a style the musicians term “tropical flamenco.”

Ambroise explains his move in this direction in a soft but emphatic tone. “The acoustic guitar has always been my favorite instrument,” he says. “I was always interested in playing Spanish music; I was one of the few guitars players in Haiti who would ever play flamenco tunes.” The dictates of earning a living, however, required him to play compas to survive. He finally tired of playing the Haitian standard, he says, in great part because he felt detached from the audience: Compas is played in the dark. Ambroise believes couples come to concerts primarily to dance with their partners, not to see the band. “It’s like no one is paying attention to you,” he says with exasperation. “It’s hard to be playing for five hours in your little corner, and no one sees you. No one cares. To me, it’s not fair.”

Ambroise pops a tape into a VCR to illustrate the point that Strings’ music makes you feel good, regardless of the context in which you hear it. Strings’ latest music video unfolds on the television screen. The image of Haiti is much different from the one of poverty and suffering that most outsiders likely envision. Children and young women with broad, toothy smiles groove to Strings’ infectious rhythms near a campfire, dancing as a long stretch of Edenic Haitian coastline unspools behind them. Ambroise says the way Strings’ members dress, the way they interact with their audience, and the way they act onstage are all part of the trio’s performance, and points that differentiate them from other Haitian bands.

That distinctiveness is beginning to earn the group some important local exposure. Recently Strings was chosen from more than twenty bands to play at a Miami party for prominent donors to the United Way. Staco says the organizers wanted “something different, something exotic.” And the response? The audience loved it, Staco declares.

“You should have seen it when the host announced that Strings was from Haiti,” he recalls, beaming. “People were like, ‘Haiti? Did he say Haiti?’ Immediately they started saying, ‘Hmm, Haiti.'” That’s precisely the kind of interest Staco and Strings hope to arouse. Both the Haitian diaspora and the Haitian domestic record market remain relatively small in economic terms, particularly for a group seeking to carve out a nontraditional niche for themselves. Staco believes if the musicians in Strings are going to make it as self-supporting artists, they need to sell outside of the tried-and-true avenues. To attain that goal, however, the group believes the marketing muscle of a major-label contract is required, something that remains elusive. In the meantime Strings will concentrate on building its name on the road, touring through Miami, Atlanta, New York City, Guadeloupe, Martinique, and France. The group’s unconventional sound may not yet be particularly lucrative, but the real payoff comes as soon as the trio takes the stage. As Ambroise says, “That’s when we finally get to perform!”