The Haitian singer Beken, whose government name is Jean Prosper Dauphin1, was discovered (though not for the first time) in 2010, on the streets of earthquake-wracked Port-au-Prince. Photographer Simon Romero caught a snatch of one his songs through the window and (without understanding the Kreyol in which Beken sings) thought its artful melancholy captured the post-catastrophe mood. Eventually Romero found the singer himself in a camp of displaced persons on the Place Saint Pierre in Pétionville—suffering, like most the capital’s population, from grief, shock, and dire deprivation. Still, Beken’s spirit was strong, and so was his voice. When Thirty Tigers producers Chris Donohue and David Macias heard the short clips of his singing in a slide show Romero had produced for the New York Times website, they were inspired to find a way to make the album now in your hands.

Beken was born in Port-au-Prince in 1956. When he was twelve he lost a leg in a car accident. In Haiti a cripple without means is condemned to the life of a malere—one of the permanently wretched of the earth. Luckier than many, Beken attended Saint Eternité School, which serves disabled children, and managed to complete high school by the age of nineteen–more education than most Haitians can win. If the song “Bakaloreya” has the facts straight, he might have gone on to university, if not for the death of his mother.

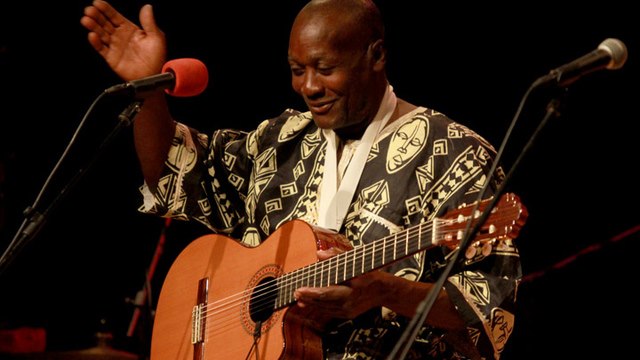

Beken’s father used to sing regularly for a peasant organization. Soon after the loss of his leg, Beken picked up a guitar and began to get into Haitian music. “I’ve had this wooden guitar a long time,” Beken sings in “Kote’w Te Ye.” At some point the instrument became his meal ticket. His music falls in Haiti’s twoubadou tradition; like most European cultural phenomena, the model of the troubadour has not passed through Haiti without transformation. Some twoubadou recycle international pop music into a Haitian idiom, others become such stinging political gadflies that they risk assassination; one of the latter, Manno Charlemagne, became mayor of Port-au-Prince on the strength of the acerbic political commentary presented in his songs.

Beken’s political material is less controversial, and his lyrics tend to be far less personal than those of a First World singer-songwriter. Another role of the twoubadou is to reflect the listeners’ own feeling back, and Beken really excels at that. Everything in Haiti is shared, and for all Beken’s lifetime there has been plenty of suffering to go round. My suffering is also yours, his songs propose, and my dream of a better life is yours as much as mine.

This message, in Beken’s gently mournful phrasing, has won the singer a few cycles of success, especially in the 1980s when he was able to tour the United States. But in the Haitian music world (where pirating was endemic for decades before digital recording made it inevitable) popularity and prosperity are not the same thing. Beken’s old records are sold all over the capital, but not for his benefit. Thanks to profoundly anti-Haitian U.S. immigration policy, Thirty Tigers’ efforts (since 2013!) to bring him to this country have failed. So Beken, wherever he is today, is probably still singing for his supper. “I don’t need anything—nothing!” he has said. “Just a guitar, a bottle, and some old pen, and I am going to sing a lot. Beken has a lot of things in his head that he has not yet sung.” – Madison Smartt Bell